69 releases (36 breaking)

| 0.46.0 | Jul 2, 2023 |

|---|---|

| 0.44.2 | Mar 25, 2023 |

| 0.41.1 | Dec 2, 2022 |

| 0.38.6 | Sep 15, 2022 |

| 0.2.0 | Nov 30, 2021 |

#1368 in Hardware support

49 downloads per month

Used in 10 crates

(9 directly)

1MB

18K

SLoC

rust-hdl

** Write FPGA Firmware using Rust! **

RustHDL is a crate that allows you to write FPGA firmware using Rust!

Specifically, rust-hdl compiles a subset of Rust down to Verilog so that

you can synthesize firmware for your FPGA using standard tools. It also

provides tools for simulation, verification, and analysis along with strongly

typed interfaces for making sure your design works before heading to the bench.

The workflow is very similar to GPU programming. You write everything in Rust,

including an update kernel that compiles down onto the hardware. You can simulate

and verify everything from the safety and comfort of your Rust environment, and

then head over to standard synthesis tools to get files that program your FPGA.

Links

You may want:

Features

- Safe - have Rust check the validity of your firmware with strongly typed interfaces at compile time, as well as at run time, synthesis, and on the device.

- Fast - Run simulations of your designs straight from your Rust code, with pretty good simulation performance.

- Readable - RustHDL outputs Verilog code for synthesis and implementation, and goes through some effort to make sure that code is readable and understandable, in case you need to resolve timing issues or other conflicts.

- Reusable - RustHDL supports templated firmware for parametric use, as well as a simple composition model based on structs.

- Batteries Included - RustHDL includes a set of basic firmware widgets that provide FIFOs, RAMs and ROMs, Flip flops, SPI components, PWMs etc, so you can get started quickly.

- Free - Although you can use RustHDL to wrap existing IP cores, all of the RustHDL code and firmware is open source and free to use (as in speech and beer).

- Tested - RustHDL has been used to write firmware that is shipping in commercial products. This includes quite complicated designs that use nearly all of a moderately sized FPGA, and take advantage of specialized hardware in the FPGAs themselves.

Quickstart

The definitive example in FPGA firmware land is a simple LED blinker. This typically involves a clock that is fed to the FPGA with a pre-defined frequency, and an output signal that can control an LED. Because we don't know what FPGA we are using, we will do this in simulation first. We want a blink that is 250 msec long every second, and our clock speed is (a comically slow) 10kHz. Here is a minimal working Blinky! example:

use std::time::Duration;

use rust_hdl::docs::vcd2svg::vcd_to_svg;

use rust_hdl::prelude::*;

const CLOCK_SPEED_HZ : u64 = 10_000;

#[derive(LogicBlock)] // <- This turns the struct into something you can simulate/synthesize

struct Blinky {

pub clock: Signal<In, Clock>, // <- input signal, type is clock

pulser: Pulser, // <- sub-circuit, a widget that generates pulses

pub led: Signal<Out, Bit>, // <- output signal, type is single bit

}

impl Default for Blinky {

fn default() -> Self {

Self {

clock: Default::default(),

pulser: Pulser::new(CLOCK_SPEED_HZ, 1.0, Duration::from_millis(250)),

led: Default::default(),

}

}

}

impl Logic for Blinky {

#[hdl_gen] // <- this turns the update function into an HDL Kernel that can be turned into Verilog

fn update(&mut self) {

// v-- write to the .next member v-- read from .val() method

self.pulser.clock.next = self.clock.val();

self.pulser.enable.next = true.into();

self.led.next = self.pulser.pulse.val();

}

}

fn main() {

// v--- build a simple simulation (1 testbench, single clock)

let mut sim = simple_sim!(Blinky, clock, CLOCK_SPEED_HZ, ep, {

let mut x = ep.init()?;

wait_clock_cycles!(ep, clock, x, 4*CLOCK_SPEED_HZ);

ep.done(x)

});

// v--- construct the circuit

let mut uut = Blinky::default();

uut.connect_all();

sim.run_to_file(Box::new(uut), 5 * SIMULATION_TIME_ONE_SECOND, "blinky.vcd").unwrap();

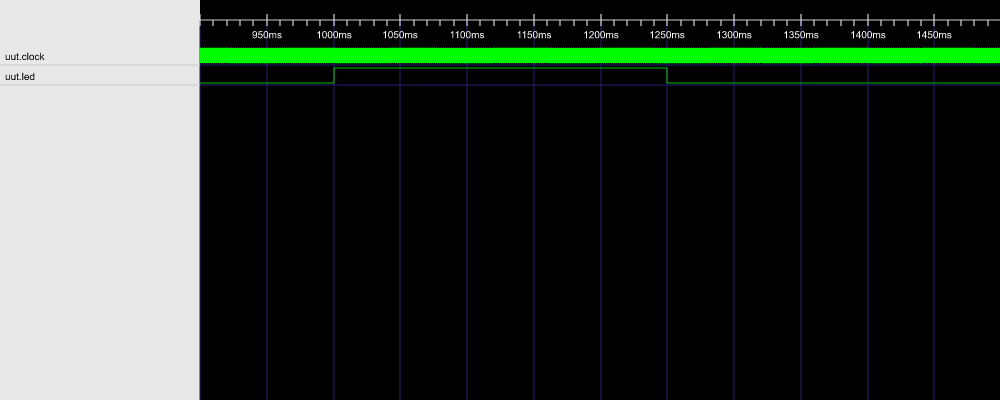

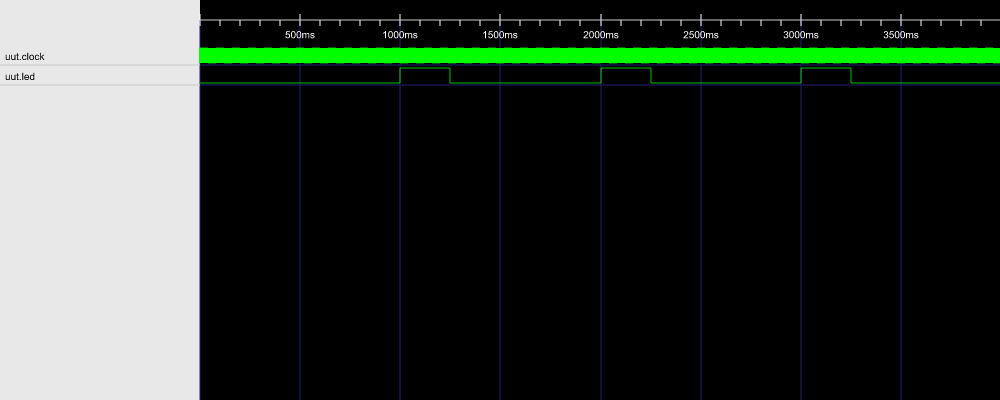

vcd_to_svg("/tmp/blinky.vcd","images/blinky_all.svg",&["uut.clock", "uut.led"], 0, 4_000_000_000_000).unwrap();

vcd_to_svg("/tmp/blinky.vcd","images/blinky_pulse.svg",&["uut.clock", "uut.led"], 900_000_000_000, 1_500_000_000_000).unwrap();

}

Running the above (a release run is highly recommended) will generate a vcd file (which is

a trace file for FPGAs and hardware in general). You can open this using e.g., gtkwave.

If you have, for example, an Alchitry Cu board you can generate a bitstream for this exampling

with a single call. It's a little more involved, so we will cover that in the detailed

documentation. It will also render that vcd file into an svg you can view with an ordinary

web browser. This is the end result showing the entire simulation:

The flow behind RustHDL is the following:

- Circuits are modelled using simple

structs, composed of other circuit elements and signal wires that interconnect them. - A

#[derive(LogicBlock)]annotation on the struct adds autogenerated code needed by RustHDL. - You

impl Logicon yourstruct, and provide thefn update(&mut self)method, which is the HDL update kernel. - That gets annotated with a

#[hdl_gen]attribute to generate HDL from the Rust code - You can then simulate and synthesize your design - either in software, or by using an appropriate BSP and toolchain.

The rest is detail. Some final things to keep in mind.

- RustHDL is a strict subset of Rust. The

rustccompiler must be satisfied with your design first. That means types, exhaustive enum matching, etc. - The goal is to eliminate a class of mistakes that are easy to make in other HDLs with checks taking place at compile time, via static analysis at run time, and then with testbenches.

- Although the performance can always be improved, RustHDL is pretty fast, especially in release mode.

License: MIT

Dependencies

~8.5MB

~154K SLoC