2 unstable releases

| 0.2.0 | Apr 12, 2023 |

|---|---|

| 0.1.0 | Jan 8, 2023 |

#2109 in Algorithms

25 downloads per month

30KB

619 lines

Regular Spatial Hashing

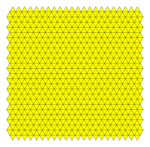

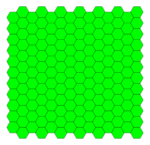

This is an experiment in order to determine whether an algorithmic modification to Spatial Hashing in 2D can reduce the amount of space that is queried. Specifically, rather than querying a cube grid, using a regular triangle grid or a hexagonal grid can possibly introduce some benefits as shown below.

Why other kinds of regular tilings?

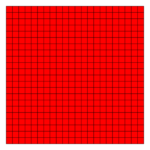

Most Implementations use the cube grid (right and red). What we're interested in improving is

the efficiency of a circular query around a point. Specifically, the goal is to maximize

query_radius/total_area_searched. Since query_radius is fixed, the problem becomes

minimizing

total_area_searched. Within a certain radius, it only necessary to search neighbors directly

adjacent to a given tile, so the focus of this is that case, since many use cases, such as

particle collision detection, use a fixed radius.

For a square grid, the area efficiency is

r : 9r^2, which is effectively the baseline since it is most common.

For a hexagon grid, the area efficiency is

r : 7 * 3√3/2 r^2 = 18.18.

And for a triangle grid, the area efficiency is

r : 13/√3 r^2 = 7.505 r^2.

Note that r here corresponds to the height of an equilateral triangle, not its side length.

Thus, by using a triangle grid, there is a slight improvement to area efficiency.

Area efficiency is important, because it directly correlates to the number of points that must be checked that are within a certain distance. For example, if points are uniformly distributed, we would expect the number of points to be directly proportional to the total searched area. Thus, by reducing searched area for a given query, we should get an approximately equiaveltn speedup.

Does Area Efficiency actually matter?

Now the next question is whether or not area efficiency actually matters for improving wall-clock performance, as opposed to only in theory.

Why might it not work?

- Additional Overhead:

- Since there are more neighbors for a single triangle, hashing may become the overhead

- There may be more hash collisions since there are more neighbors, and thus more false-positives.

Because there are clearly reasons for and against it, it is necessary to just benchmark it.

Results In Practice

Note:I while these results are interesting, probably for a first implementation there is not much benefit to changing from squares.

To compare the effectiveness of each kind of spatial hash, I made a simple plinko toy, which drops many balls amongst a set of equispaced pegs. The balls do not (currently) collide with each other, but they collide with the pegs, so they must be checked for intersection at each step. To do, so I use a spatial hash, and my implementation uses an enum for which kind of coordinate system to use. Then, at run-time, it simply initializes the pegs with each set of coordinates, and runs the demo.

In the demo, there are 3 reported values:

- FPS: frames per second, which is related to the speed it takes to prepare each frame

- #Checks: The number of intersection pairs which are actually checked, even if they are rejected

- And Frame Duration in milliseconds, which reports how long each frame takes to compute.

We find that #checks directly corresponds to the area difference, with cubes being

approximately 14k, triangles being 11k, and hexagons being 28k. Thus, if the number of

point-point intersection checks is the bottleneck when using a cubic spatial hash, it might be

good to switch to a triangle coordinate system.

Surprisingly though, we find that this does not directly correlate with the speed of the

resulting demo, finding hexagons to be the fastest despite requiring more checks. This is

likely because the time required to perform hashing for neighbors of hexagons is 7/9 that of

cubes, whereas triangles is 13/9. Since there are a relatively high number of balls, this also

becomes a bottleneck. If instead we were to be querying a single point against many more pegs,

we may find different results.

Thus, when actually considering which to use in practice, it would be best to benchmark all three approaches and see which one actually does well.

Methodology

Why must it be Regular?

Another question you may ask is why the tiling is only triangles, hexagons, and squares? This is because they are the only regular polygonal tilings of the 2D plane.

Why is a regular tiling good? There are a few key properties that make regularity good.

- First, no tile is different than the next, so there is no special casing.

- Second, it is easy to determine the neighbors of a tile in regular tiling.

And for practical purposes:

- Regular tilings are better understood than random tilings, so there are blogs and existing implementations.

- It is easy to understand regular tilings, and they are symmetric. It is not clear why an irregular tiling could bring any benefit.

Does this extend to 3D?

While this implementation is only for 2D, the next obvious question would be whether or not 3D spatial hashes could benefit from this.

The answer is not immediately yes, as the only regular polytope (3D equivalent of a polygon) that tessellates 3D space. Instead, it can easily extend it to hexagonal and triangular prisms. A 3D spatial hash can use hexagonal hashing for two of the dimensions, (i.e. X & Y), and use grid spacing in the third (Z) dimension. This will still lead to higher volume efficiency.

Resources

- Wikipedia.