11 releases

| 0.2.5 | Jul 26, 2024 |

|---|---|

| 0.2.4 | Jul 26, 2024 |

| 0.2.2 | May 10, 2024 |

| 0.1.5 | May 4, 2024 |

#307 in Concurrency

933 downloads per month

Used in 4 crates

(3 directly)

33KB

361 lines

k-lock

A mutual exclusion primitive useful for protecting shared data

This mutex will block threads waiting for the lock to become available. The

mutex can be created via a [new] constructor. Each mutex has a type parameter

which represents the data that it is protecting. The data can only be accessed

through the RAII guards returned from [lock] and [try_lock], which

guarantees that the data is only ever accessed when the mutex is locked.

Difference from std::sync::Mutex

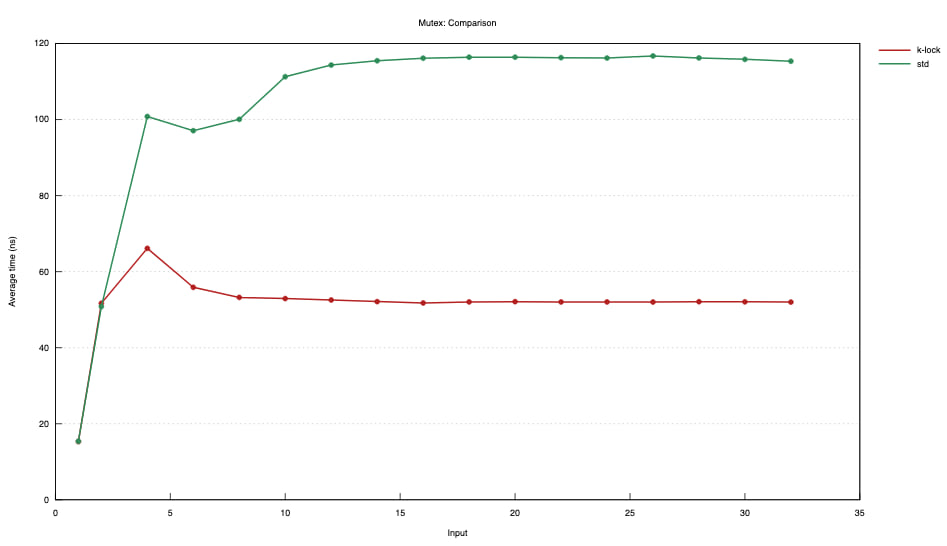

16 threads, short critical section expression: *mutex.lock() += 1;

Mac OS

This lock is not optimized for Mac OS at this time. The quick way to lock on

Mac OS is via pthread_mutex, which is not currently implemented in k-lock. If

you need your mutex to perform well on Mac OS, you need to use std::sync::Mutex.

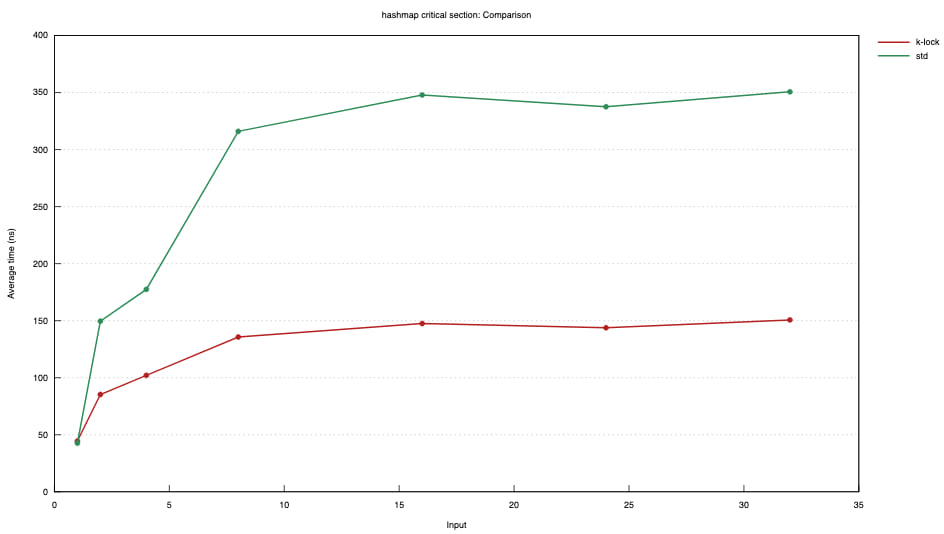

AWS c7g.2xlarge aarch64

Tiny critical section

Hashmap critical section

Thread count is on the X axis.

About

This mutex is optimized for brief critical sections. It avoids syscalls by spinning as long as the lock is making fast progress. It also aggressively wakes multiple waiters per unlock when it is heavily contended.

In some cases, std::sync::Mutex may be better. As always, profiling and measuring

is important. This mutex is tested to outperform std::sync::Mutex on brief locks

that work with a HashMap but further research is needed to determine suitability for

wider timespans.

Much of this mutex implementation and its documentation is adapted with humble

gratitude from the venerable std::sync::Mutex.

Poisoning

The mutex in this module uses the poisoning strategy from std::sync::Mutex.

It is expected that most uses of this mutex will be to lock().expect("description")

to propagate a panic from one thread onto all synchronized threads.

Examples

use std::sync::Arc;

use std::thread;

use std::sync::mpsc::channel;

use k_lock::Mutex;

const N: usize = 10;

// Spawn a few threads to increment a shared variable (non-atomically), and

// let the main thread know once all increments are done.

//

// Here we're using an Arc to share memory among threads, and the data inside

// the Arc is protected with a mutex.

let data = Arc::new(Mutex::new(0));

let (tx, rx) = channel();

for _ in 0..N {

let (data, tx) = (Arc::clone(&data), tx.clone());

thread::spawn(move || {

// The shared state can only be accessed once the lock is held.

// Our non-atomic increment is safe because we're the only thread

// which can access the shared state when the lock is held.

//

// We unwrap() the return value to assert that we are not expecting

// threads to ever fail while holding the lock.

let mut data = data.lock().unwrap();

*data += 1;

if *data == N {

tx.send(()).unwrap();

}

// the lock is unlocked here when `data` goes out of scope.

});

}

rx.recv().unwrap();

To unlock a mutex guard sooner than the end of the enclosing scope, either create an inner scope or drop the guard manually.

use std::sync::Arc;

use std::thread;

use k_lock::Mutex;

const N: usize = 3;

let data_mutex = Arc::new(Mutex::new(vec![1, 2, 3, 4]));

let res_mutex = Arc::new(Mutex::new(0));

let mut threads = Vec::with_capacity(N);

(0..N).for_each(|_| {

let data_mutex_clone = Arc::clone(&data_mutex);

let res_mutex_clone = Arc::clone(&res_mutex);

threads.push(thread::spawn(move || {

// Here we use a block to limit the lifetime of the lock guard.

let result = {

let mut data = data_mutex_clone.lock().unwrap();

// This is the result of some important and long-ish work.

let result = data.iter().fold(0, |acc, x| acc + x * 2);

data.push(result);

result

// The mutex guard gets dropped here, together with any other values

// created in the critical section.

};

// The guard created here is a temporary dropped at the end of the statement, i.e.

// the lock would not remain being held even if the thread did some additional work.

*res_mutex_clone.lock().unwrap() += result;

}));

});

let mut data = data_mutex.lock().unwrap();

// This is the result of some important and long-ish work.

let result = data.iter().fold(0, |acc, x| acc + x * 2);

data.push(result);

// We drop the `data` explicitly because it's not necessary anymore and the

// thread still has work to do. This allow other threads to start working on

// the data immediately, without waiting for the rest of the unrelated work

// to be done here.

//

// It's even more important here than in the threads because we `.join` the

// threads after that. If we had not dropped the mutex guard, a thread could

// be waiting forever for it, causing a deadlock.

// As in the threads, a block could have been used instead of calling the

// `drop` function.

drop(data);

// Here the mutex guard is not assigned to a variable and so, even if the

// scope does not end after this line, the mutex is still released: there is

// no deadlock.

*res_mutex.lock().unwrap() += result;

threads.into_iter().for_each(|thread| {

thread

.join()

.expect("The thread creating or execution failed !")

});

assert_eq!(*res_mutex.lock().unwrap(), 800);

Dependencies

~0–10MB

~43K SLoC